The arm you offer up for vaccination could impact your immediate immune response. But here's the catch: scientists still aren't sure if it's better to give a secondary booster shot to the same arm or a different one.

Currently, only a handful of studies have explored whether you should switch sides between a first and second jab, and the ones on COVID vaccines have produced mixed results.

Following the 2020 outbreak of COVID-19, for instance, researchers in Germany found that giving multiple jabs to the same arm produced better immune responses two weeks later.

Then, a follow-up study from researchers in the US found the exact opposite. According to that randomized trial, switching arms between shots resulted in a four-fold increase in COVID-specific antibodies four weeks after the second jab.

Get ready for yet another contradictory finding. Researchers in Australia are weighing in on the debate, and their experiments on mice and humans agree with the same-arm study.

The trial, led by Rama Dhenni from the Garvan Institute of Medical Research and Alexandra Carey Hoppé from the University of New South Wales (UNSW), involved 30 healthy participants who had not yet had COVID-19.

All participants received two shots of the Pfizer vaccine, three weeks apart – 20 had both shots in the same arm, while 10 got the booster in the opposite arm to the first jab.

Those in the same-arm group showed a boosted immune response in the week after their second shot, according to blood and lymph node analysis.

"Those who received both doses in the same arm produced neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 significantly faster – within the first week after the second dose," explains Carey-Hoppé.

"These antibodies from the same arm group were also more effective against variants like Delta and Omicron," adds immunologist Mee Ling Munier from UNSW.

Still, the apparent immune boost from a same-arm vaccination was ultimately short-lived. Four weeks after the booster, those who received a jab in the same arm showed similar antibody levels to those who received a jab in the opposite arm.

This suggests that the strengthened immune response from same-arm vaccinations does not last longer than a month.

"If you've had your COVID jabs in different arms, don't worry – our research shows that over time the difference in protection diminishes," says Munier. "But during a pandemic, those first weeks of protection could make an enormous difference at a population level."

Further research is needed, but Munier suspects that this same-arm vaccine strategy could help achieve herd immunity faster.

To explore why that might be, Munier and colleagues used mouse models. When mice were given a second vaccine to the same side of the body, it increased their immune response in that side's lymph nodes.

Lymph nodes drain fluid from their respective sides of the body. When a vaccine is administered to one arm, it introduces the corresponding lymph node to a weakened pathogen (or its components).

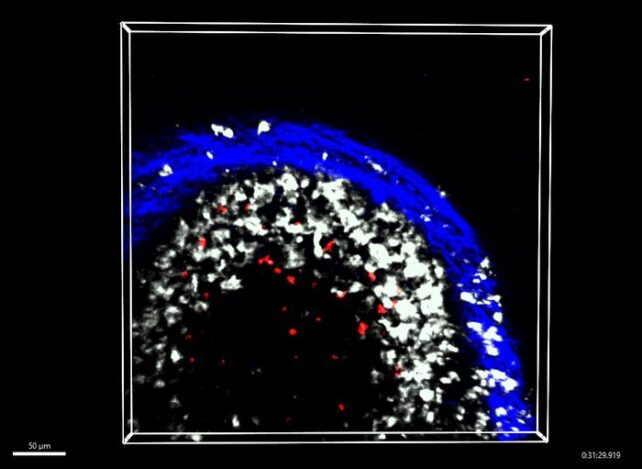

Immune cells called macrophages, which guard the entry point to the lymph nodes, handcuff these invaders and take them to unique players called memory B cells (Bmems).

These long-lived cells memorize what the danger looks like for future reference, and they also enter a specialized factory within the lymph node to trigger the production of antibodies tailored to that specific invader.

In mouse models, when a second vaccine was given to the same side of the body, the draining lymph node's sentinel macrophages were already primed to respond to that threat.

This means they jumped to action faster, communicating with "large clusters of reactivated Bmems" to send 10 times as many Bmems into the antibody factory as the non-draining lymph node.

Similar to the mouse data, when 18 of the human participants had their lymph nodes biopsied with a fine needle, the researchers found those who received a same-arm jab had increased percentages of Bmems in these antibody factories.

While these results are intriguing and shed some much-needed light on how vaccines work to boost our immune systems, Dhenni and colleagues argue further research is needed to make any practical recommendations.

The new findings may be more relevant to initial boosters given in quick succession, for instance, not necessarily seasonal vaccines that can be given months, if not years, apart, when immune responses on both sides of the body have time to balance out.

"This is a fundamental discovery in how the immune system organizes itself to respond better to external threats – nature has come up with this brilliant system and we're just now beginning to understand it," says immunologist Tri Phan.

The study was published in Cell.