Detecting Alzheimer's disease earlier means better support and more treatment options, and gives scientists extra opportunity to study the disease. Now, new research could bring the diagnosis time forward by more than a decade in some cases.

An international team of researchers has discovered that in people with a genetic predisposition to Alzheimer's, a particular biomarker in the blood could signal the disease up to 11 years ahead of cognitive symptoms appearing.

The biomarker is the protein beta-synuclein, and can be identified with a simple blood test. It's an indicator of damaged contacts between neurons in the brain, and its links to dementia are becoming increasingly well established.

"Blood levels of this protein reflect neuronal damage and can be determined relatively easily," says neurologist Patrick Öckl, from the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases.

"In this, we see a potential biomarker for the early detection of neurodegeneration."

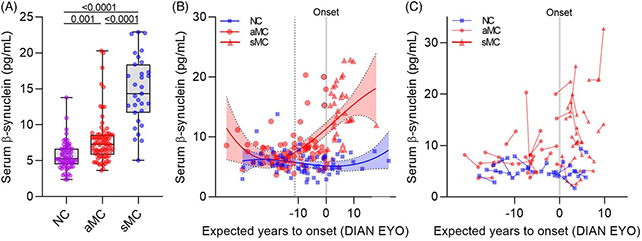

The researchers looked at blood samples from 178 individuals registered with an Alzheimer's research database. The participants were a mix of people, in terms of their visible symptoms of dementia, and having the genetic mutations linked to Alzheimer's.

Through statistical modeling, the team found higher beta-synuclein levels in the blood of asymptomatic mutation carriers compared to those without the mutation, and the highest levels in symptomatic carriers. That's strong evidence that the protein is tied to the earliest damage associated with dementia.

These study participants weren't all followed over time, but references to the typical progression of Alzheimer's and the development of symptoms suggest that checking for this protein could provide more than a decade of early warning.

This makes sense when you know how beta-synuclein works: it's found in the connections (or synapses) between neurons, and when these connections are broken, the protein is released. That this apparently happens early on in the development of dementia gives us more clues as to how dementia first gets started, as well.

"Loss of brain mass and other pathological changes that also occur in Alzheimer's disease do not happen until later," says neurologist Markus Otto, from University Medicine Halle in Germany.

"After the onset of symptoms, the more severe the cognitive impairment, the higher the beta-synuclein level in the blood. Thus, this biomarker reflects pathological changes in both the pre-symptomatic and symptomatic stages."

This biomarker has potential beyond early diagnosis. The researchers think monitoring levels of beta-synuclein could help in identifying how quickly Alzheimer's is progressing, and how effective certain treatments are at protecting neurons. It could even help measure brain damage from other conditions, such as a stroke.

But primarily, the goal is to diagnose Alzheimer's disease as early as possible. Promising new treatments like amyloid antibodies can delay the onset of symptoms by years, but they tend to work better when administered early.

"At the moment, Alzheimer's is usually diagnosed quite late," says Öckl. "Thus, we need advances in diagnostics. Otherwise, we won't be able to tap the full potential of these new drugs."

Testing for beta-synuclein levels in at-risk patients could help make the most of these treatment advances.

The research has been published in Alzheimer's & Dementia.