Upon learning about the blood vessels responsible for our water-soaked finger wrinkles, young readers of The Conversation's Curious Kids series had further questions for scientists:

"Do the wrinkles always form in the same way?" one asked.

"And I thought: I haven't the foggiest clue!" recalls the author of the educational article, biomedical engineer Guy German from Binghamton University in New York . "So it led to this research to find out."

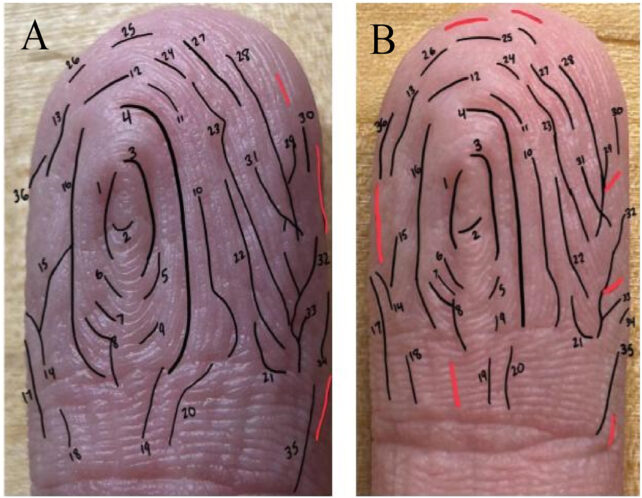

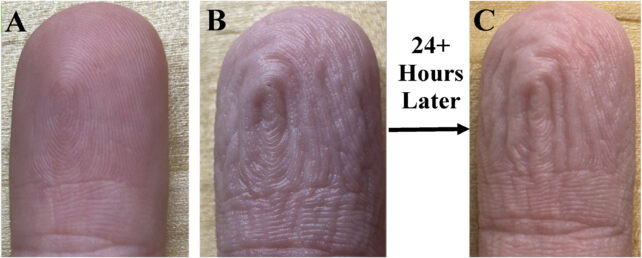

German and his colleague Rachel Laytin recruited three volunteers to soak their fingers for 30 minutes. Images confirm the patterns of looped peaks and valleys adorning the participants' sodden fingertips mostly repeated themselves when they were soaked again 24 hours later.

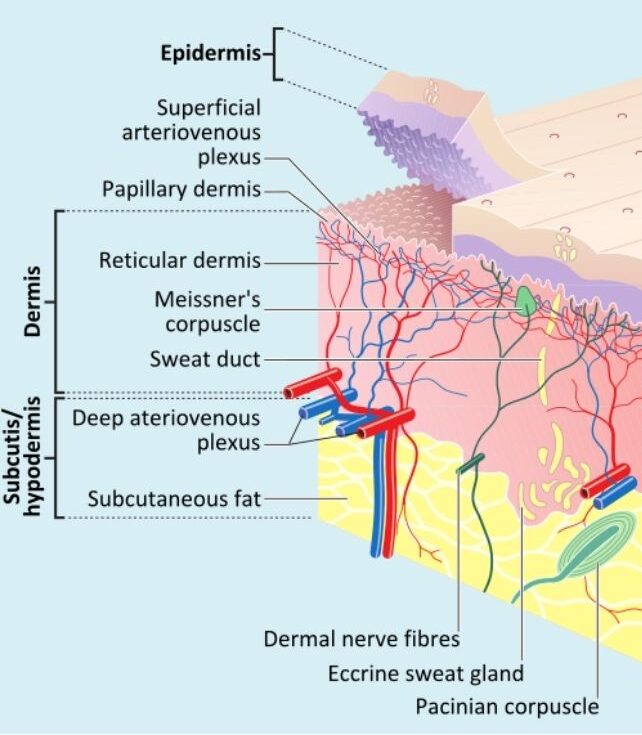

As water seeps through open sweat ducts into our skin, it eventually decreases the concentration of salt in our outer layer. Nerve fibers alert the brain to this change in skin condition, which then triggers our bodies' automatic blood vessel retraction.

When these tiny skin vessels shrink, they drag the surface of our largest organ down with them, shriveling once-smooth fingers and toes into a rougher, pruney texture.

"Blood vessels don't change their position much – they move around a bit, but in relation to other blood vessels, they're pretty static," explains German. "That means the wrinkles should form in the same manner, and we proved that they do."

This puckering isn't just a random side-effect either. The morphological changes create a measurable advantage in wet conditions: the skin's temporary grooves and ridges provide a better grip, making it easier for us to walk on or grasp sodden things.

As these wrinkles give us super grip it seems odd we don't keep them full time. While researchers don't know why this is, they suspect the temporary texture might reduce our finger's sensitivity or make them more vulnerable to injury.

It was originally assumed that swelling caused soaked skin to wrinkle, but a study in 2016 revealed our skin would need to swell at least 20 percent for that to happen. What's more, previous research found people with nerve damage don't experience finger pruning, leading to further investigation of the mechanisms involved.

"We've heard that wrinkles don't form in people who have median nerve damage in their fingers," says German. "One of my students told us, 'I've got median nerve damage in my fingers.' So we tested him – no wrinkles!"

In addition to sating childlike curiosity, such details can assist in forensics. For example, understanding this finger skin distortion could help identify bodies after prolonged water exposure after natural disasters.

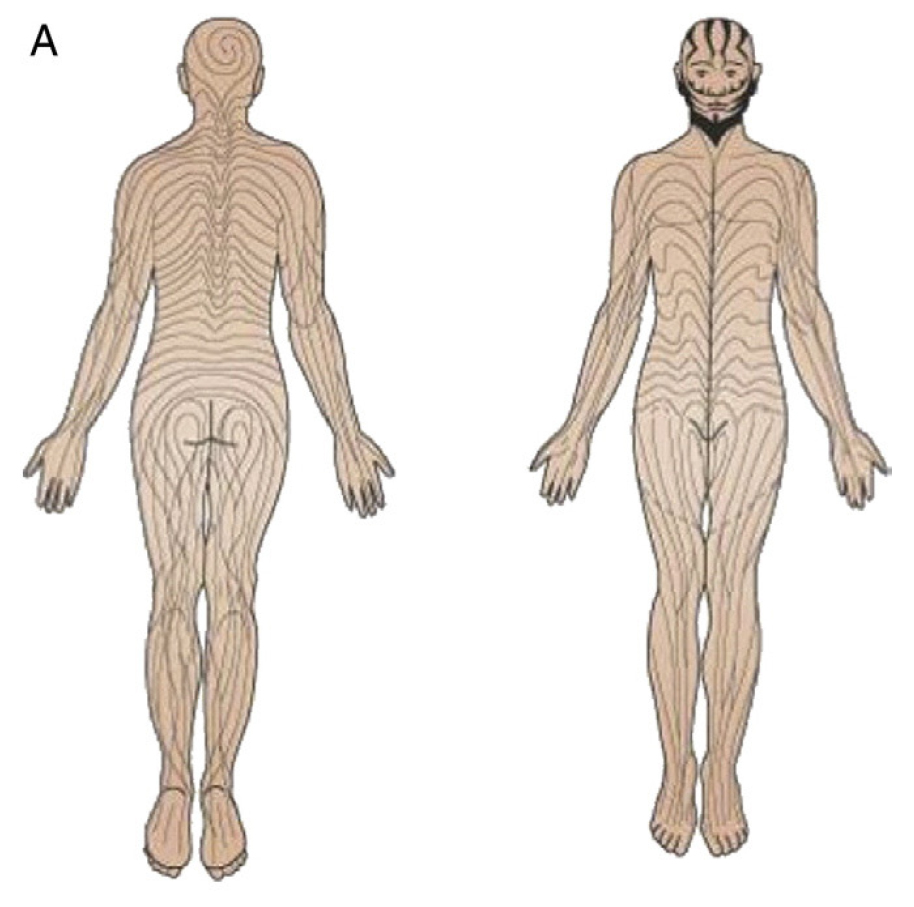

So we can now add wrinkle topology to the set of consistent patterns that compose our skin, along with fingerprints and hidden stripes we all possess.

This research was published in the Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials.