New research has shown how the parasitic amoeba Entamoeba histolytica takes bites from your cells to use as a disguise, hiding them from the immune system.

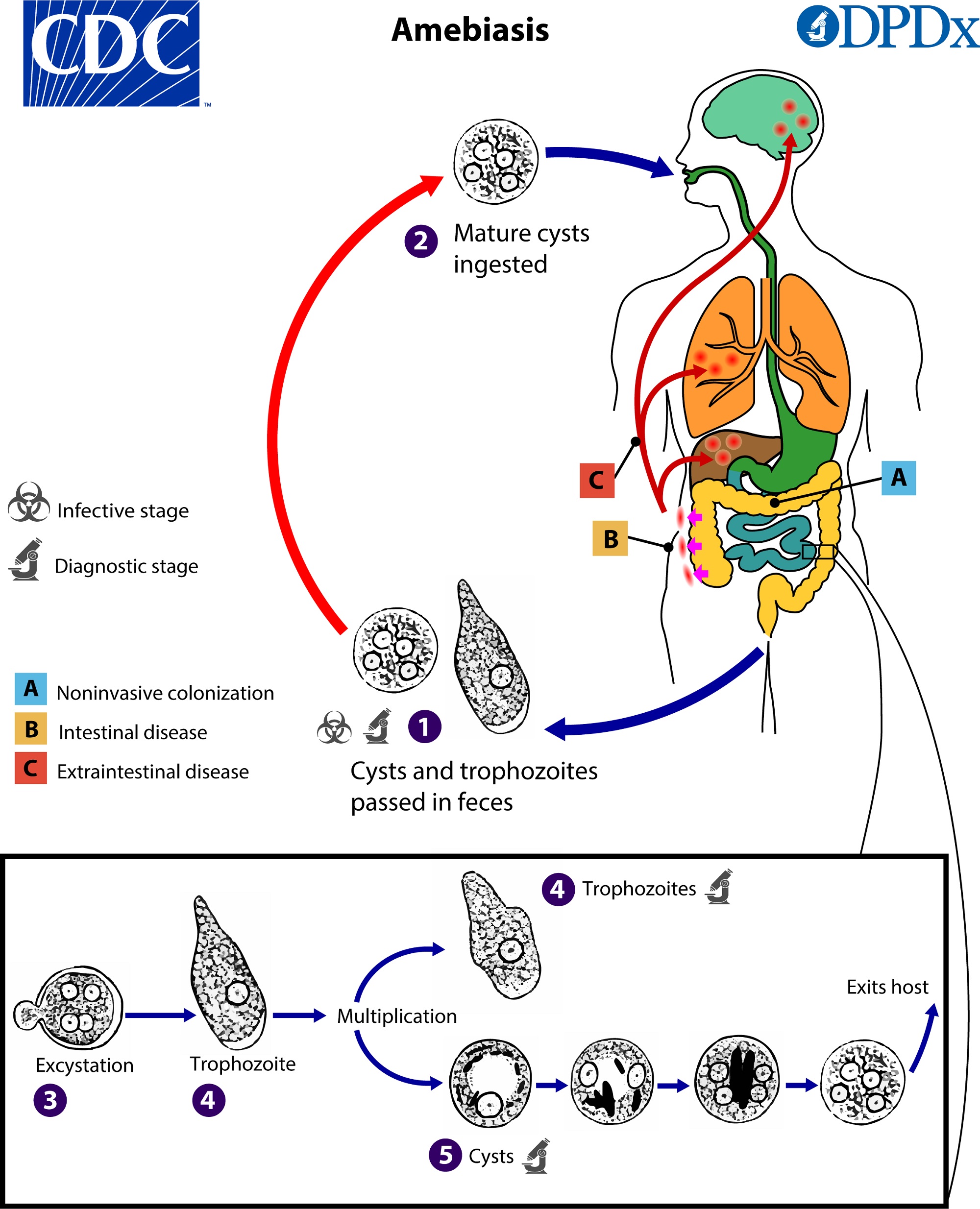

Entering the body via contaminated food or water, most infections from the parasite cause diarrhea, if any symptoms at all. In particularly bad cases, the amoeba can spread via the bloodstream to other vital organs, where it can cause serious problems.

If the infection reaches the liver, for instance, the amoebic abscesses it creates can be fatal, causing complications that claim the lives of almost 70,000 people each year.

Exactly how this tiny monster wreaks such havoc in its host was largely unknown, until microbiologist Katherine Ralston – currently at the University of California Davis, but back then posted at the University of Virginia – investigated the amoeba more closely in 2011.

The going theory was that E. histolytica injected a poison into its victim cells. But Ralston saw something very different going on through her microscope. E. histolytica was taking what looked like actual bites out of human cells.

"To devise new therapies or vaccines, you really need to know how E. histolytica damages tissue," Ralston says. "You could see little parts of the human cell being broken off."

Stranger still, the amoeba seemed satisfied with just a few chomps from each cell's membrane before moving on to its next victim, leaving in its wake a slew of half-chewed cells with cytoplasms oozing from their puncture wounds.

"It can kill anything you throw at it, any kind of human cell," Ralston says. It can even take a chomp out of the white blood cells that are meant to swallow such intruders.

Now, Ralston and her colleagues Maura Ruyechan and Wesley Huang have discovered this seemingly wasteful habit actually allows E. histolytica to gather outer membrane proteins from the human cells, which it proceeds to arrange on the surface of its own body for protection against defences in the blood.

Surprisingly, this disguise doesn't just protect it from human immune 'guards': it works on immune responses present in the blood of other species, too.

"It has become clear that amoebae kill human cells by performing cell nibbling, known as trogocytosis," the authors write. "After performing trogocytosis, amoebae display human proteins on their own surface and are resistant to lysis [rupture] by human serum [a component of blood]."

This molecular disguise prevents our immune system from launching an attack on the amoeba by presenting chemical tags that identify it as safe, a bit like stealing the ID off a security guard. When E. histolytica dons the human proteins CD46 and CD55, it can safely scoot past the 'complement proteins' tasked with tracking down and destroying foreign cells.

This allows it to continue chomping away, forming abscesses full of liquified cells in the organs it inhabits.

Intriguingly, the team conducted an experiment in which they allowed the amoeba to collect material from human cells before exposing the 'disguised' parasites to mouse blood serum.

"Although mice are not a natural host of E. histolytica, experimental infection of mice with amoebae mimics many aspects of the human infection, ranging from immune responses to the host genetic determinants of susceptibility to infection," the authors write.

Its camouflage was effective despite originating from an entirely different species, reflecting similarities between human and mouse complement protein security systems. This knowledge will allow the researchers to further investigate treatments and vaccines for the amoeba using mouse models, before proceeding to human trials.

"Science is a process of building," Ralston says. "You have to build one tool upon another, until you're finally ready to discover new treatments."

This research has not yet been peer-reviewed, but it is available as a pre-print in bioRxiv.