Long before Tyrannosaurus rex stalked the planet, a Dragon Prince reigned supreme. Paleontologists have discovered a new 'missing link' species that cleared the way for the iconic giant carnivores.

The new mid-size tyrannosaur, which lived about 86 million years ago, has been named Khankhuuluu mongoliensis – a name that translates to "Dragon Prince of Mongolia" in honor of where it was found.

"We wanted to capture that Khankhuuluu was an early and smaller species, so a prince, rather than a king like its much larger tyrannosaur descendants," Darla Zelenitsky, paleontologist at the University of Calgary in Canada, tells ScienceAlert.

Together with fellow UCalgary paleontologist Jared Voris, Zelenitsky co-led a study describing the new species based on two partial skeletons that had been gathering dust in a museum collection since the early 1970s.

As far as famous 'tyrant lizard' predators go, Khankhuuluu was a middleweight. It stood about 2 meters (6.6 feet) tall at the hips, was twice that long nose-to-tail, and tipped the scales at around 750 kilograms (1,650 pounds). By comparison, T. rex was estimated to grow up to 13 meters long and weigh up to 8.8 tonnes.

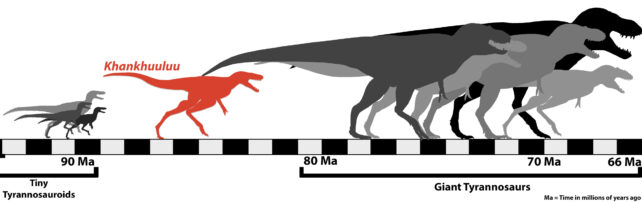

Of course, evolving to such a massive size didn't happen overnight. It was long presumed that these colossal apex predators evolved from tiny ancestors, like Suskityrannus and Moros intrepidus, which both stood around 1 meter tall.

Logically, the road between those two extremes should be paved with middle-sized species. The fossil record has been patchy in that regard, unfortunately. Khankhuuluu, which lived some 20 million years earlier than Tyrannosaurus, helps plug that gap.

"Khankhuuluu represents a transitional form from some even smaller 'tyrannosauroid' ancestors to those giant apex predator tyrannosaurs," Voris tells ScienceAlert.

"It had long, slender legs, likely making a very agile predator, and its skull was lightly built, not capable of delivering such powerful bone crushing bite forces as its tyrannosaur descendants."

Its discovery also implies a complicated history for tyrannosaurs. Khankhuuluu hailed from what is now Asia, far from where its more giant relatives would appear in North America. Over a span of a few million years the family gave rise to a range of massive species like Gorgosaurus and Thanatotheristes before returning across the Bering land bridge.

Back in Asia, tyrannosaurs diversified again, this time into two distinct clades: Tyrannosaurini, which were massive apex predators with deep snouts like Tarbosaurus; and Alioramini, which were smaller and had long, narrow snouts like Qianzhousaurus.

Eventually, some of the Tyrannosaurini wandered back to North America to try to make it big in Hollywood, leading to household names like Tyrannosaurus rex.

Evolution probably would have continued playing this ancient game of Catan if it wasn't for that asteroid flipping the table and losing most of the pieces about 66 million years ago.

Signs of this back-and-forth journey are in agreement with other recent studies on tyrannosaur family history. It also helps explain why the closest-known relative of T. rex isn't, say, Daspletosaurus — which stalked the same turf just 10 million years earlier – but is instead Tarbosaurus, a cousin that lived a whole continent away.

The study also finds some interesting quirks in how tyrannosaurs in North America and Asia filled different ecological niches.

"Both the North America and Asian ecosystems had mid-sized predators that were tyrannosaurs, but this was achieved in different ways," Zelenitsky tells ScienceAlert.

"In Asia, there were two very different forms of tyrannosaur species in the same ecosystem. Forms like Tarbosaurus would have filled the giant apex predator role, whereas the alioramins were the smaller, fleet-footed, mid-sized predators."

But it turns out that T. rex was such a spotlight-hog that it claimed both niches for itself.

"In the last 2 million years of the Cretaceous Period, just before the mass extinction event, Tyrannosaurus was the only tyrannosaur in North America that we know of," says Zelenitsky.

"The juveniles were smaller, fleet-footed animals with shallow snouts that would have taken down smaller prey than their adult counterparts. They would have essentially filled the mid-sized predator niche, rather than the apex predator niche of the adults."

Of course, none of this would have been possible without the overlooked middle children like Khankhuuluu. We welcome the new prince to the dinosaur royal family, alongside the king (and, if you believe some controversial studies, the queen and the emperor).

The research was published in the journal Nature.