Historians have for a long time believed that leprosy was introduced to the Americas by European settlers, but the latest research offers strong evidence to the contrary – suggesting that Indigenous Americans had already been dying of the disease for centuries.

The primary cause of leprosy is a bacterium called Mycobacterium leprae, and the researchers still think this was introduced to America by Europeans. However, it seems a lesser-known culprit was already established by that time.

A new study from an international team of researchers found that another bacterium, Mycobacterium lepromatosis – a less common cause of leprosy infection – was present in the DNA of ancient human remains from Canada and Argentina dating back at least a thousand years.

"This discovery transforms our understanding of the history of leprosy in America," says genomicist Maria Lopopolo, from the Institut Pasteur in France.

"It shows that a form of the disease was already endemic among Indigenous populations well before the Europeans arrived."

The M. lepromatosis bacteria was first discovered in a patient in the US in 2008, and since then it's also been found in red squirrels (Sciurus vulgaris) in the UK. It may well have spread from the US to the UK in the 19th century, the researchers suggest.

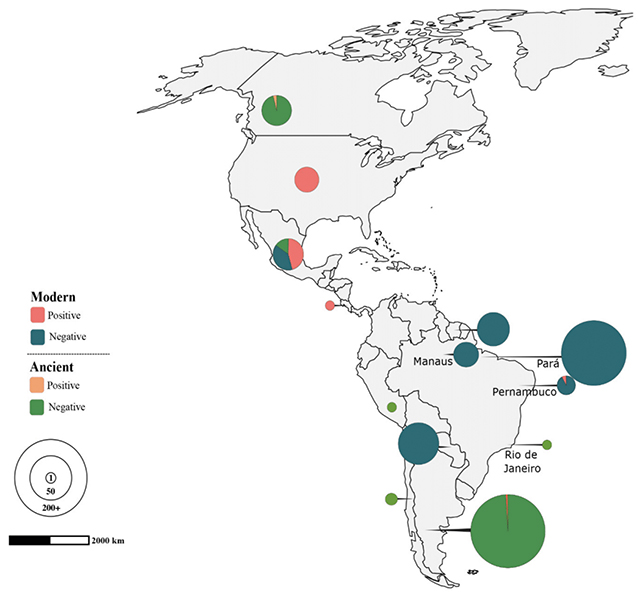

In partnership with local Indigenous communities in terms of handling ancestral remains, the researchers analyzed the DNA from a total of 389 ancient and 408 modern human samples. From the results, they put together a genetic family tree of leprosy bacteria.

Even though they were thousands of kilometers apart, the ancient Canadian and Argentinian samples were remarkably genetically similar. That points to a rapid spread of M. lepromatosis across the American continents.

Based on the timeline put together from the DNA, the different strains of M. lepromatosis would have split from a common ancestor more than 9,000 years ago. With that many millennia of evolution under its belt, the team says there are likely even more diverse forms of the bacteria still waiting to be discovered in the Americas.

"We are just beginning to uncover the diversity and global movements of this recently identified pathogen," says biologist Nicolás Rascovan, from the Institut Pasteur. "The study allows us to hypothesize that there might be unknown animal reservoirs."

This all adds a valuable extra layer to our understanding of the history of the Americas, and of leprosy. It gives researchers some incredibly useful data points in terms of the progression and diversification of the disease.

Infectious diseases play an important part in the story of North, South, and Central America, with the arrival of Europeans introducing a host of new pathogens that Indigenous communities weren't biologically prepared for.

Now we know that the leprosy part of the picture is a lot more complicated than we previously realized. Around 200,000 new cases of the disease are reported worldwide every year, though it can now be treated and cured with modern drugs.

"This study clearly illustrates how ancient and modern DNA can rewrite the history of a human pathogen and help us better understand the epidemiology of contemporary infectious diseases," says Rascovan.

The research has been published in Science.