Scientists are looking at ways to tackle Alzheimer's and dementia from all kinds of angles, and a new study has identified the molecule hevin (or SPARCL-1) as a potential way of preventing cognitive decline.

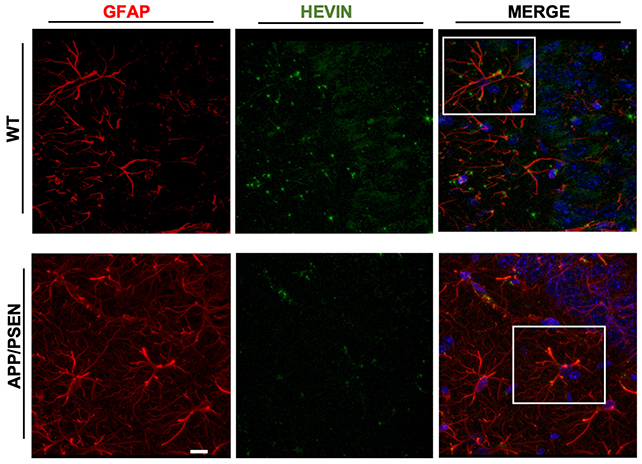

Hevin is a protein naturally produced in the brain by cells called astrocytes. These support-worker cells look after the connections or synapses between neurons, and it's thought that hevin plays a role in this essential work.

In this new study, researchers from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and the University of São Paulo in Brazil boosted hevin production in the brains of both healthy mice and those with an Alzheimer's-like disease.

That hevin overload worked wonders: over six months of testing, the treated mice demonstrated better memory and learning capability than untreated animals, while brain scans showed improved neuron communication across synapses.

"Hevin is a well-known molecule involved in neural plasticity," says neurobiologist Flávia Alcantara Gomes from UFRJ.

"We found that the overproduction of hevin is capable of reversing cognitive deficits in aged animals by improving the quality of synapses in these rodents."

Further analysis showed that the additional hevin in the mouse brains was triggering the production of other proteins related to synapse health. It seems hevin isn't working alone when it comes to maintaining neuron connectivity.

The research team also looked at the wider context, digging into publicly available health data to find that hevin levels in the brains of Alzheimer's patients were lower than normal. That suggests hevin and astrocytes do have a role to play in the disease.

"The originality lies in understanding the role of the astrocyte in this process," says Gomes.

"We've taken the focus away from neurons, shedding light on the role of astrocytes, which we've shown could also be a target for new treatment strategies for Alzheimer's disease and cognitive impairment."

It will take a significant amount of time to go from lab tests in mice to actual treatments that people with dementia are able to take, of course, but it's a promising start – and eventually, treatments based on these findings could complement other drugs.

Many of the treatments currently being explored for Alzheimer's look to tackle the toxic protein clumps that build up in the brain, but those protein bundles aren't targeted by hevin. In fact, the new research showed hevin had no impact on plaque build-up, which could support the emerging idea that they aren't a 'cause'.

"Although there's still no consensus among researchers, I work with the hypothesis that the formation of beta-amyloid plaques isn't the cause of Alzheimer's," says Felipe Cabral-Miranda, biomedical scientist at UFRJ.

"And the results of the study, by providing proof of concept for a molecule that can reverse cognitive decline without affecting beta-amyloid plaques, support the hypothesis that these, although involved in the mechanisms of the pathology, aren't enough to cause Alzheimer's."

It's a complex picture, and while we're still not sure how Alzheimer's disease gets started in the brain, it's probable that numerous factors are involved. That means any potential treatment or prevention is going to need to be complex as well.

"Of course, in the future it'll be possible to develop drugs that have the same effect as hevin," says Gomes.

"For now, however, the fundamental benefit of this work is a deeper understanding of the cellular and molecular mechanisms of Alzheimer's disease and the aging process."

The research has been published in Aging Cell.